After one month in office, the Biden administration has fundamentally changed how the federal government responds to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In direct contrast to his predecessor, President Joe Biden is treating this as a national-scale crisis requiring a comprehensive national strategy and federal resources. If that sounds familiar, it should: It’s a return to a traditional – and in many ways proven – approach to disaster management.

The Trump administration deviated dramatically from established emergency management practices. It politicized public health and related decision-making processes and overrode the disaster response roles of federal agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Among other things, the Trump administration established an entirely new coordination structure headed by a White House task force, then changed the lead federal agency from Health and Human Services to FEMA. Those moves, combined with a disjointed array of other operational task forces, made it difficult to create an integrated response. Even basic data collection from hospitals for tracking the coronavirus’s spread was thrown into disarray by changes.

The Biden administration is now reempowering key federal agencies to return to the roles and responsibilities they were designed for within a planned national disaster management structure.

Our own work in hazards management, with both governments and nongovernmental organizations, has shown us that fidelity to proper process and respect for expertise is essential to effective disaster management. The Biden administration’s approach to the pandemic so far suggests this is the model it will follow.

What Federal Emergency Response Was Designed to Do

By design, the U.S. federal system for managing disasters is decentralized and tiered.

The system is structured so that local governments take the lead in managing hazards and responding to local emergencies. But when an emergency becomes a disaster-scale problem, state and federal governments should be prepared to provide financial assistance and other support, particularly logistical support.

FEMA, established in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter, has a crucial role as a national emergency management coordinator. Just getting all levels of government to work together effectively, along with private and nonprofit organizations, represents a massive challenge. Major crises over the years, including the Sept. 11 terror attacks, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, have helped refine federal strategies and processes and improve preparedness for future disasters – including pandemics.

Pandemic preparedness has been a part of U.S. emergency management planning since at least 2003. The H1N1 bird flu crisis in 2009 triggered the passage of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Authorization Act in 2013. That law established Health and Human Services as the lead federal agency, and the statute specifically addresses the development of medical surge capacity, pandemic vaccine and drug development and more.

Managing a pandemic is more challenging than other types of disasters. Unlike a wildfire or tornado, which strikes a specific place for a limited period of time, a global pandemic is all-encompassing, affecting all jurisdictions and every economic sector. It requires focused coordination between public health and emergency response bureaucracies within government and with other key partners such as hospitals.

Given the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government normally would have taken the lead in coordinating the response and assistance. Instead, the Trump administration devolved primary responsibility for the pandemic response to state and local governments, despite their limited capacity.

This approach was doomed to fail. It muddled use of the National Response Framework and created a competitive environment for state and local governments as they scrambled for supplies. It sidelined the agencies involved in pandemic preparedness, such as the CDC and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and it ignored specific plans for a pandemic response. It also politicized resource allocation choices and undermined, through misinformation, the importance of public health behaviors such as wearing masks.

Biden’s Return to Established Practices

Against this backdrop, the Biden administration’s early efforts to return to established disaster management practice underscore the importance of leadership of complex systems used to address complex problems.

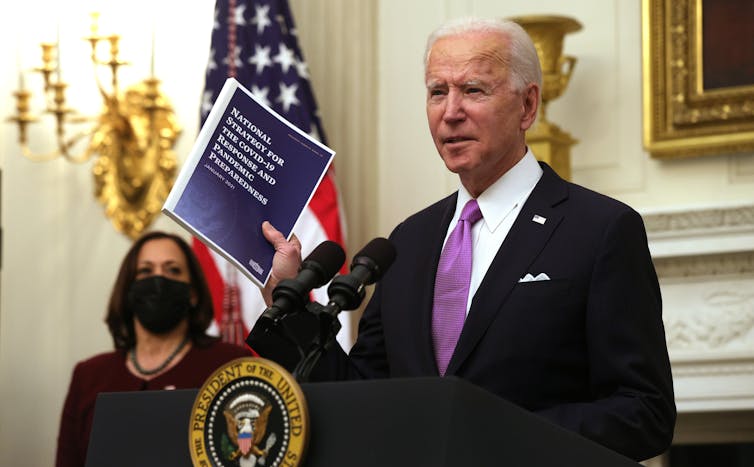

The list of changes in the month since Biden took office is extensive. The administration issued a comprehensive national strategy for pandemic response. It increased the involvement of FEMA and the Department of Defense to support vaccination distribution, expanded COVID-19 testing for underserved populations and rejoined the World Health Organization, which Trump had pulled out of. Biden also invoked the Defense Production Act to mobilize private industry to ramp up production of test kits, vaccines and personal protective equipment. The administration is now advocating for a national COVID-19 relief package in Congress.

The Biden administration’s rapid, strategic reorientation of the federal government to manage the pandemic has parallels for other complex challenges, including developing a national strategy for addressing climate change. Continuing to refine these processes, including proper management of the federal bureaucracy, and public investments aimed at reducing risk should be priorities for the administration.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Brian J. Gerber Brian J. Gerber is an Associate Professor in the College of Public Service and Community Solutions, Arizona State University. He is Co-Director of the ASU Center for Emergency Management and Homeland Security and is Director of the Master of Arts in Emergency Management and Homeland Security degree program. He is an Honorary Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales (Australia), a Senior Sustainability Scholar with the Wrigley School of Sustainability, Arizona State University and a PLuS Alliance Fellow. Dr. Gerber’s research interests and publications include work on disaster policy and management, homeland security policy, and environmental regulation, publishing in a variety of journals in those areas. He has held various administrative leadership positions, including directing a policy research institute and several graduate degree programs. At present, he sits on the executive committee of the National Council for Public-Private Partnerships, is an editorial board member of several academic journals and is Editor-in-Chief of Natural Hazards Governance, Oxford University Press. Dr. Gerber has led catastrophic incident planning projects, has designed, led and facilitated various emergency exercises, and has conducted key program evaluations and policy analyses on topics ranging from large-scale disaster evacuations to pandemic preparedness. His applied work on disaster management has included partnerships with federal, state and local government agencies, as well as with numerous nonprofit organizations, both in terms of research and evaluation and direct volunteerism during disaster incident response. He has received research grants from the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Education, the West Virginia Department of Military Affairs and Public Safety, the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals and the Colorado Department of Public Safety, among others.

Melanie Gall is a Clinical Professor and Co-Director, Center for Emergency Management and Homeland Security, Watts College, Arizona State University. Gall is a hazards geographer studying the interaction between natural hazards and society. She utilizes geospatial analytics and disaster metrics to capture these interactions. Her expertise lies in risk metrics (e.g., disaster losses, indices, risk assessments), hazard mitigation and climate change adaptation planning as well as environmental modeling. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of South Carolina, M.S. from the University of Salzburg (Austria), and a B.S. from the University of Heidelberg (Germany).

This article is courtesy of The Conversation.